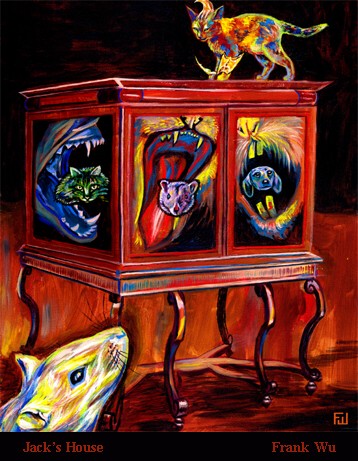

"Jack's House," by Frank Wu, for the book Greetings from Lake Wu, illustrating the story by Jay Lake. Published by Wheatland Press.

Writing an introduction to a piece of artwork is a weird thing, because you are describing a visual thing with words, and words (discounting the art form of typography) are not images but ideas. Laurie Anderson, quoting Steve Martin, said that writing about music was like dancing about architecture. It's like that.

For this introduction, I was even thinking about lifting a phrase from Harlan Ellison. For one story in his collection Shatterday, Ellison wrote a beautifully succinct one-sentence introduction: "I have nothing to say about this story."

I felt that way the first time I thought this painting was done.

Then I thought about what John Lennon once said. He had been asked what he thought of when he re-heard an old Beatles tune he'd recorded years ago. He said he remembered the circumstances in which it was recorded, the people.

So... when I think of this painting, a seemingly unrelated little phrase comes into my mind: "My name, Jose Jimenez." Seemingly unrelated. The story and painting are about rats, cats and dogs fighting with each other. And Jose Jimenez has nothing to do with that. For those who don't know, Jose Jimenez, a character created by comedian Bill Dana, had various adventures in the early sixties, most famously as a reluctant astronaut. Example: Ed Sullivan to Jose: Is that a crash helmet? Jose: I hope not. Example 2: Jose: The most important thing in rocket travel is the blast-off. I always take a blast before I take off. Otherwise I wouldn't go near that thing.

I think of Jose Jimenez as I look at this painting, because he appeared in The Right Stuff, which I was watching as I painted this and the other last paintings for this book, "Tall Spirits" and "The Goat Cutter." I needed to see this film then, because this was the week the Columbia died.

Jose Jimenez really struck a chord with me, because he made me laugh. When the Mercury astronauts went into space, we knew it was really dangerous. Our rockets regularly blew up in dramatic, horrific fireballs. Every safety precaution was taken, but there were really good odds that no matter what you did, no matter how good a pilot you were, the huge rocket under you could just explode without warning. (Don't worry, this really is connected to this painting, we'll get back to it, you'll see. Thanks.)

As I was saying... Only half a year before the first men went into space, as they say, something happened with a Soviet R16 at its secret launching pad in Kazakhstan. The rocket was fully loaded, but leaked fuel and had a balky new flight control system. Under intense pressure from the Kremlin to hurry up and launch, Marshall of Artillery Mitrofan Nedelin went to the launch pad for an inspection. He was violating all safety protocols, sitting in a chair meters from the rocket, barking orders at dozens of engineers, military staff of all ranks, political overseers and other civilians - all standing on the launch pad. Suddenly the second stage of the rocket ignited, exploding the fuel tank directly below. A fireball expanded out 120 meters in diameter; 90 people died, most instantly burned beyond recognition, some dying in hospitals later.

While no Americans have died in launch pad explosions, Americans were familiar with our rockets blowing up and our boys botching it, too. And there were other, unexpected dangers, too. Mercury astronaut Gus Grissom completed the second manned American flight, safely landing his spacecraft in the water. But the escape hatch prematurely blew, and Gus fell into the water and nearly drowned. A few years later, Gus and two other heroes died in a fire sitting on the launch pad atop Apollo I. They had less than a minute after detecting the fire. The astronauts, suffocating and burning up, struggled to open the command module's inner hatch, which was actually impossible because of the high air pressure inside the module. Technicians outside the module first ran for their lives, then returned with gas masks and fire extinguishers, fighting through dense poisonous smoke to find the tools needed to open up the ship. But within a minute, possibly within thirty seconds, it was already too late.

Jose Jimenez made fun of the fear and the danger. He made it all palatable.

In the decades since the Apollo I fire, there were no accidents, no deaths in the American space program except the horrific Challenger explosion. But that was in 1986, which now seems like a lifetime ago. And then there was the gallows humor, the tasteless Christa McAuliffe jokes, but somehow that made things feel better. How did Christa McAuliffe and her husband divide up the housechores? He fed the dog and she fed the fish. In all this time, we had forgotten how dangerous space travel was and is. Until now.

And so now the Columbia is gone, and we return to Jose Jimenez. Is that a crash helmet? I hope not.

(And now we reach the part wherein this Author assembles the various pieces he's thus far presented to the Patient Reader.)

After finishing this painting the first time, and thinking about this introduction and thinking about Jose Jimenez, I looked up the Harlan Ellison book to check the quotation. In Shatterday, Harlan wrote about how authors need to fearlessly stir people up, to force them confront their inner demons. In writing one story, he had come to the horrific realization that he wanted his mother gone. Not dead, not that, because that would be too terrible. But just gone. She had been deathly ill on and off for years, and hadn't been happy in ages. She was marking her days, and he was caring for her the way she had cared for him as a child. But he was drained and tired and exhausted, and sick of waiting for the inevitable to happen. And he just wanted it to be over, for her to be gone. And he felt ungrateful and scummy to make this realization, and hated himself for that. And when he said this on the radio, one woman whose mom had died of cancer said, Thank you for that, because I felt the same way and felt guilty, too, and I thought I was the only one. And now that it was out in the open, this horrible feeling could be dealt with.

And then, at that moment, I realized that the painting was not finished. Not done even though I had scanned it and shown it to Deb Layne, who dubbed it "Beautiful." Yeah, Beautiful maybe, but not done. And worst, it was dishonest.

The originally finished version of the painting still had the cat at the top and the mouse at the bottom, but they are as far apart as they could be and still be on the same canvas. The open jaws of the dog, cat and rat were there, but safely contained in little boxes. Everything tidy and safe, the personal demons in little cages. Maybe this was my way of dealing with the psychological distress of the Columbia disaster. Putting everything in boxes. This painting was my Jose Jimenez.

But upon reading Ellison's words, I realized that I had also snuffed out the horrific aspects of the story. This, like many of Jay's stories, has a nasty and unpleasant edge. Cats and dogs don't fight each other with ridiculous electronic gadgets; there is no comedic banter between them. Animals are ripped apart, flesh is torn asunder. Cute things die.

In order to finish the painting, I had to paint things inside the open jaws. It was then that I inserted the cute mouse - and he had to be cute - inside the cat's jaws. The cat - and he had to be cute - inside the dog jaws. The cute dog inside the rat's jaws.

Now it's done.

The world is a harsh place. There. Now I've said it. Perhaps there is a time for Jose Jimenez, and there is a time to mourn and grieve and lance the wound. No, the mouse is not safe, far from the cat. The jaws are not in neat little boxes. Danger is indeed everywhere, we just didn't want to see it before. Not just from terrorists, but from simply living on this planet. All living things die, some violently, some quietly as part of what Disney euphemistically called the Circle of Life. The world is a harsh place and children die, babies die, favorite grandmothers die, kittens and puppies die, even cute ones with floppy ears. Sometimes cute things are eaten by ugly things, sometimes thousands of people die in acts of senseless stupidity, and sometimes good people are blown up and burned beyond recognition 200,000 feet in the sky.

But you probably knew all that already. So let me go on and ask a question: How can a good God allow bad things to happen to good people? I do not ask this, because this question assumes that anything outside of what we personally would have planned is a Bad Thing, and it thus assumes that we should be God, and it assumes that there should be no death and no sickness and no pain and no stupidity and no jealousy and no irresponsible destruction in this world, which are all unrealistic hopes. So I do not ask this question.

Rather, I ask, Dear Lord, how to we respond when bad things happen? What can I do to heal the hurt?

The answer for that lies is another painting in this book. In my illo for "Tall Spirits, Blocking the Night," we first see a man in the lower left hand corner. A second man is slumped before him, wretched, aged, worn out from a lifetime of woe and care and self-pity. Meanwhile, harsh and powerful spirits trample them underfoot. But the first man is showing an act of kindness to the second; he is giving him a cup of coffee. And this is what I think God wants us to do in the face of tragedy and stupidity. Show kindness and love and giving to each other. We are here to overcome evil with good. We are here to give each other hope. Now more than ever.

End of sermon.